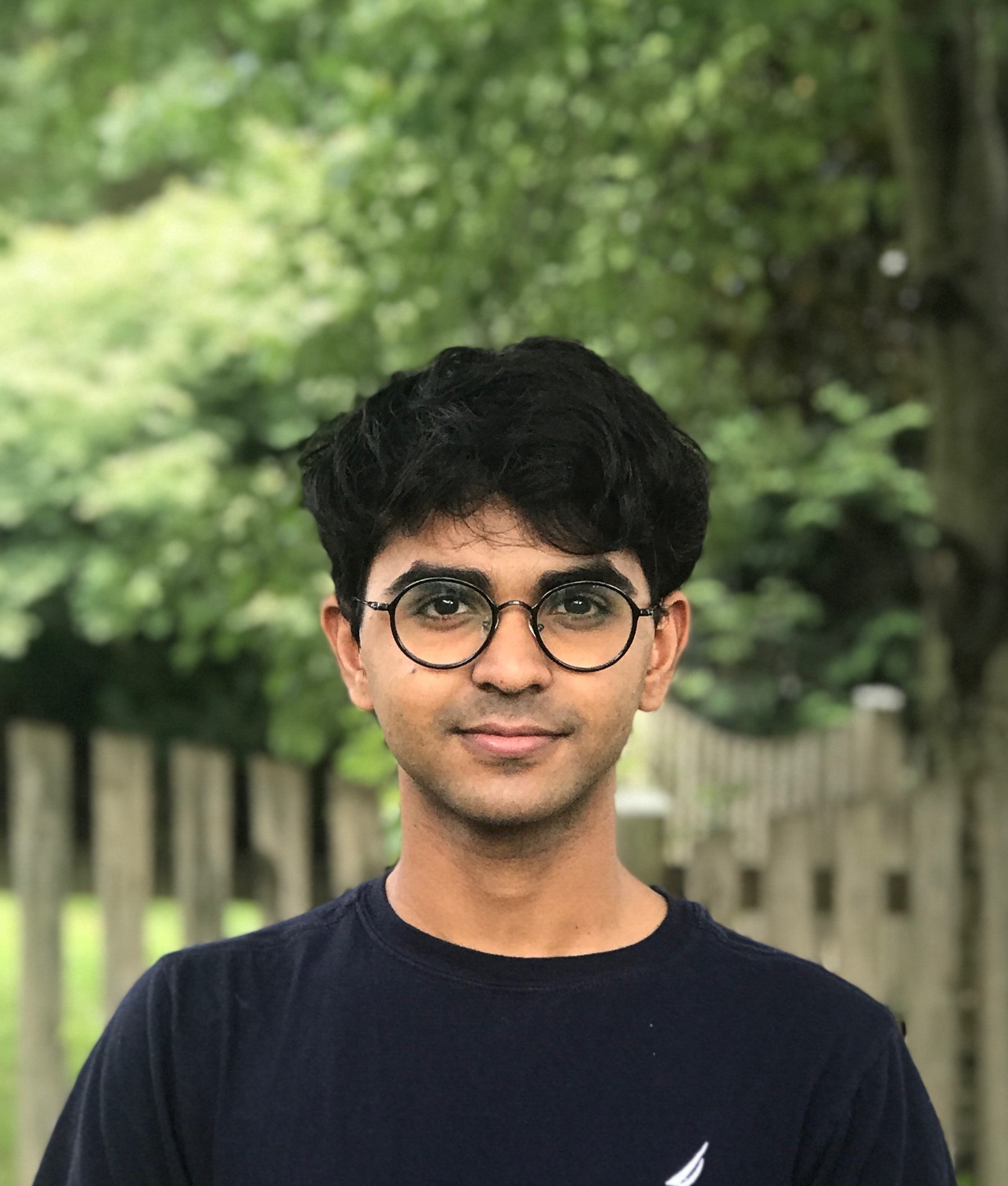

Tathagat is a senior from Lucknow, India. He studies history of science and Russian, with interests in environmental history, post-colonial histories of South Asia and the global Cold War. As a Rising Waters Fellow at the Penn Program for Environmental Humanities, he wrote about the problem of lead in Philadelphia’s drinking water from an STS perspective. He is passionate about queer advocacy, and has been a Program Assistant at the Penn LGBT Center for three years, as well as volunteered at LGBTQ rights organizations in India and Russia. In non-pandemic times, he can be found riding the El to his favorite grocery stores in Northeast Philly.

Tathagat Bhatia

Wolf Humanities Center Undergraduate Fellow

2020—2021 Forum on Choice

Tathagat Bhatia

Science, Technology, and Society

Modeling Postcolonial Development: Cold War Economics and the Politics of Neutral Expertise

In December 1961, several high-profile Indian politicians accused a group of economists at MIT’s Center for International Studies of colluding with the CIA to thwart Indian development. The critics alleged that the computer models developed by the economists were flawed in their negative assessment of India’s plans for rapid industrialization because they were rooted in political motives, rather than pure economics. While the allegations turned out to be untrue, they damaged the Center’s reputation so seriously that it had no choice but to cease its Indian operations. As many historians have remarked, such was the politicized nature of expertise during the Cold War: the perception that politics had creeped into the economic modeling was enough to sour relations, even if no such interpolation had occurred. However, these narratives create a dichotomy between economics and politics that may not really have existed. In this talk, I tease out the relationship between Cold War economics and politics by tracking the development of the linear programming models that lie at the center of this controversy. The economists hoped that their quantitative models would somehow bypass ideology, and bolster their credence in a non-aligned India wary of foreign expertise. Yet, I argue, ideology was baked into the Center’s modeling effort from the outset, ultimately contributing to its downfall. Interrogating the social production of these models allows us to decipher how the mathematized science of economic modeling, Cold War loyalties, and India’s postcolonial development dreams worked with and against each other in a transnational context.