Scholars of music, literature, and oral traditions face a challenging archive of recorded sound that dates well back into the 19th century but contains many defunct formats, ruined and seemingly unplayable wires, disks, and cylinders, and large numbers of known recordings that have not survived in any physical form at all. But new methods of digitization, and new tools for analyzing digitized music and speech, are bringing that messy archive to the forefront of current scholarship and changing the historical picture in many fields. Patrick Feaster and Tanya Clement are two of the leading experts in this new convergence between digital technologies and the humanities. Though working on different kinds of sound recordings and taking different lines of approach, both are engaged in pathbreaking research. This symposium will provide an opportunity to learn about their projects and to engage them in an open conversation about new ways to work with audio from the archives.

PATRICK FEASTER is a specialist in the history, culture, and preservation of early sound media. A three-time Grammy nominee and co-founder of the First Sounds Initiative, he has been actively involved in locating, making audible, and contextualizing many of the world's oldest sound recordings. He received his doctorate in Folklore and Ethnomusicology in 2007 from Indiana University Bloomington, where he is now Media Preservation Specialist for the Media Digitization and Preservation Initiative. He is also the current President of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections.

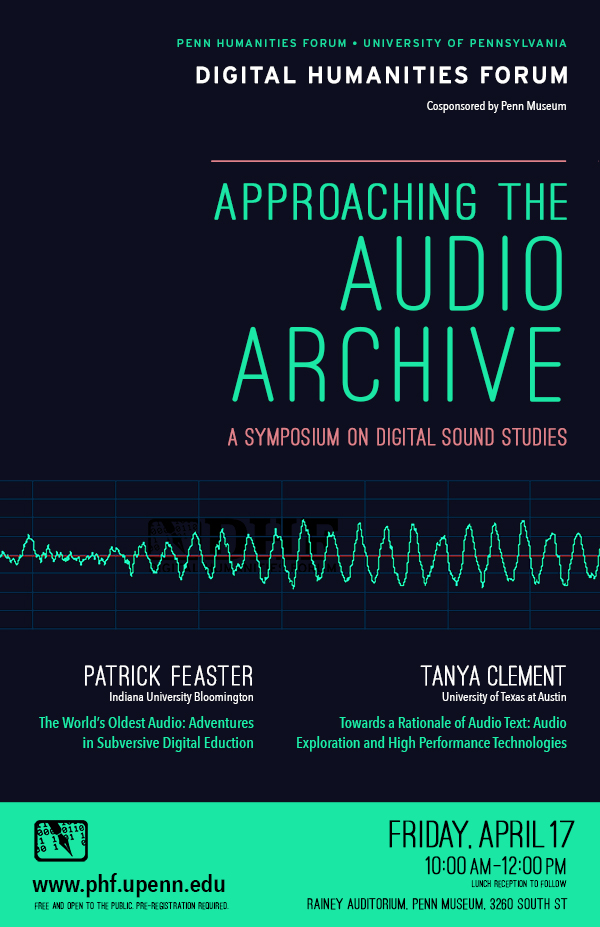

The World’s Oldest Audio: Adventures in Subversive Digital Eduction

In 2008, the First Sounds Initiative made headlines by playing back a recording of someone singing “Au Clair de la Lune” on April 9, 1860, over seventeen years before Thomas Edison invented his phonograph. The source was a waveform scratched onto soot-blackened paper by a phonautograph, an instrument designed to record aerial sound vibrations for visual study. By using digital processing to present the same information audibly, we subverted its creator’s intentions but also brought it to life, making it more accessible, intelligible, and enchanting. Since then, I’ve continued experimenting with digital methods of “educing” historical inscriptions “against the grain”—that is, of delivering their content to our senses (most often the sense of hearing) in meaningful ways unforeseen by the people who made them. In my presentation, I’ll describe several techniques I’ve been using, share some of the most striking results, and discuss the novel insights they can provide. Among other things, we’ll listen to the oldest known snippet of recorded human speech, Samuel Morse’s “first telegraph message” of 1844, and music played automatically from a medieval manuscript.

TANYA CLEMENT is an Assistant Professor in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. She has a PhD in English Literature and Language and an MFA in fiction. Her primary area of research is scholarly information infrastructure. She has published widely on digital humanities and digital literacies as well as scholarly editing, modernist literature, and sound studies. Her current research projects include High Performance Sound Technologies in Access and Scholarship (HiPSTAS).

Towards a Rationale of Audio Text: Audio Exploration and High Performance Technologies

Scholars have not had much chance to do open-ended exploratory research—what Jerome McGann calls "imagining what we don't know"—with sound collections. Although we have now digitized hundreds of thousands of hours of culturally significant audio artifacts and developed sophisticated systems for computational analysis of text, we have made little headway toward discovering such things as how prosodic features change over time and space or how tones differ between groups of individuals and types of speech, or how one poet or storyteller's cadence might be influenced by or reflected in another's. To encourage more exploratory research with sound collections, the High Performance Sound Technologies for Analysis and Scholarship (HiPSTAS) project has been using spectral analysis and machine learning to analyze folklore recordings from the University of Texas Folklore Center Archives and from Penn's own PennSound poetry archive. This talk will describe the HiPSTAS project, its findings thus far, and its efforts to merge the "close listening" practices of literary scholars and folklorists with the "distant listening" made possible by new technologies.